The United States created its first nuclear program in 1939 after President Roosevelt received the Einstein-Szilard letter, written by Leo Szilard in consultation with fellow Hungarian physicists Edward Teller and Eugene Wigner and signed by Albert Einstein. The letter indicated that the US might want to start its nuclear program to keep pace with work being done in Germany.

The project to develop atomic weapons was formalized after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 8, 1941, putting the United States in the war. Known as the Manhattan Project, it was a joint project between the US, Britain, and Canada to create the first atomic bomb. The Army Corps of Engineers managed the project under the direction of the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD). General Leslie Groves became the project director in August 1942, with the project already underway.

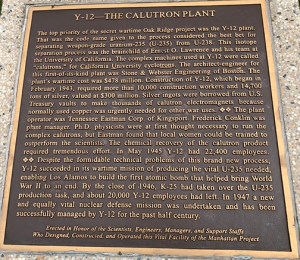

The Army Corps of Engineers determined that the project would consider all experimental ideas for creating the atomic bomb rather than focus on one, exponentially increasing the project’s scope. Five methods of creating uranium atom separation were considered, and three were developed: the electromagnetic separation method initially developed by Ernest O. Lawrence at the University of California at Berkeley became known as the Y-12 facility; the gaseous diffusion method developed became known as K-25; the liquid thermal diffusion method known as S-50; along with X-10 Graphite Reactor, the method developed under the stadium at the University of Chicago led by Enrico Fermi and included Leo Szilard, to produce plutonium.

Secret Cities and other locations

To support this development, secret cities where project employees lived and worked were created at Los Alamos, New Mexico, where the scientists who created the bombs lived and worked was known as Site Y or Project Y and had a peak population of about 6,000; Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where the enriched uranium needed for the Little Boy atomic bomb used at Hiroshima was created was known as Site X or Project X and housed the Y-12, K-25, S-50, and X-10 plants with a peak population of over 75,000; and Hanford, Washington, where the plutonium used in the Fat Man bomb dropped on Nagasaki was developed was known as Site W and had a peak population of 100,000.

Offices and Colleges

Manhattan Project offices spanned the country to provide direct contact with the many engineering and manufacturing firms that were contractors and sub-contractors on the project, as well as colleges and universities enlisted for various experiments and assessments.

Boston Office

Boston was one of those cities with a Manhattan Project Office from 1942 – 1946 when the Stone and Webster Engineering Corporation, based in Boston with offices across the country, became the first master contractor for the project. The largest projects Stone and Webster Engineering worked on were the planning and construction of the city of Oak Ridge, Tennessee, and the planning, development, and construction of the Y-12 plants at Oak Ridge.

Stone and Webster Engineering was selected for their knowledge and skills, which they have demonstrated over the past 40 or so years on a variety of projects, and their ability to work closely with established vendors, such as General Electric, Westinghouse Electric, Chapman Valve, Pfaudler, and E.B. Badger, to name a few.

Their other projects included planning and building a factory for Metal Hydrides in Beverly, MA, for the creation of powdered metals used in a variety of products and experiments; planning and building the heavy water plant in Trail, British Columbia; designing the plans for the Argonne Laboratory to expand Chicago physicists working on the pile reactor, a project that wasn’t built in Chicago but was built as the X-10 facility at Oak Ridge; planning the first bomb laboratory at Los Alamos; planning and building a large steel factory for Chapman Valve in Indian Orchard, MA; constructing the largest TNT plant ever built; and several war-related projects for the Navy.

Oak Ridge and Boston

At the start of the project in 1942, electromagnetic separation was the only uranium separation method tested and found to work. The decision to build the facilities at Oak Ridge, but until the city was built, the Army Corps of Engineers felt it was easier to bring the office to Boston than move 700+ engineers, draftsmen, and administrative support needed to a not-yet-built city.

The Boston Office had engineers (including Army Corps engineers and personnel from the University of California, Berkeley), draftsmen, and office staff. They occupied 13 floors spread over four buildings: 89 Franklin Street (Floors 3 and 4), 85 Franklin Street (Floors 2 and 3), 72 Franklin Street (Floors 3, 4, 5, 6), and 161 Devonshire Street (Floors 2, 7, 8, 9, 10). Over time, the Army engineers expanded to the 11th floor.

A few engineers, procurement, and expediting staff were in Knoxville, first in the Andrew Johnson Hotel and later in a renovated gas station. A group of senior engineers were stationed at the University of California at Berkeley to interact with Ernest Lawrence’s team to learn as much as possible about the electromagnetic separation process.

Staffing

The Boston Office began ramping up in August 1942 and struggled to find enough draftsmen through the spring of 1943 as the need for final approved plans for all parts of the project, particularly the electromagnetic plants, were reviewed and revised. From mid-July 1943 to mid-July 1944, maintained a project staff of between 700 and 800 people, with 60% of the staff comprised of engineers, draftsmen, procurement, expediters, and inspectors and 40% comprised of office staff including order typists, schedule typists, typists, stenographers, clerks, ditto operators, filing, mailing, mail distribution, messengers and guards.

The Manhattan Project worked with the War Powers Act and the War Production Board to keep the critical staff on the project and maintain the workforce needed for the planning, designing, drafting, and execution of project work.

Secrecy

Secrecy was of the utmost importance. Each time a new floor was taken over for project work, a minimum of 5 security personnel were assigned to that floor to monitor track and activity. Access was restricted to those with clearance, such as visiting Manhattan Project personnel, including General Groves and Colonel Nichols. Scientists working on the project include Ernest Lawrence and Robert Oppenheimer. Sub-contractors such as General Electric, Westinghouse, Chapman Valve, Pfaudler, etc., staff. Security lists noted who entered the floor and was restricted to the waiting area. Everyone had to sign in, and whether or not they were allowed to enter the floor was noted.

Stone and Webster employees working on the Manhattan Project and Stone and Webster employees working on non-Manhattan Project work were often housed in the same buildings, but since the project required total separation of project-related and non-project-related activities, former co-workers rarely saw one another.

Army security personnel investigated everyone working on the project and noted the dates of the security review on their personnel cards. They also kept track of visitors to other locations, including Metal Hydrides in Beverly, Harvard, and MIT.

Procurement and Expediting

While the engineers worked with the sub-contractors to determine the parts needed for the project, the procurement department worked with the engineer’s project specifications to create the contracts and orders. The expediting department maintained a traffic office to route completed parts from the vendors to the appropriate location, usually by circuitous routes to obscure the origination and the destination point of a shipment. In some cases, supplies were routed slowly or re-routed while the train companies learned the priority shipping codes being used and worked to ensure that other freight and troops made their destinations. Once, items meant for Chicago ended up in Detroit. Sometimes, items arrived before construction completion and would be held at the train yard. At one point, 645 freight cars were sitting in Knoxville’s rail yard, waiting to be claimed by Oak Ridge. When the station master refused any new shipments until the 645 freight cars were out of his yard, all workers, including all construction workers building housing and factories, were assigned to unload the freight cars. A 3-day process that affected schedules.

From Development to Production

In August 1944, Oak Ridge’s management shifted from development and construction by Stone and Webster in Boston to management by the Tennessee Eastman Corporation at Oak Ridge. Many engineers moved from Boston to Oak Ridge, while others shifted to other projects. The Boston Office continued to maintain procurement, expediting, and some engineering. The Army Corps of Engineers maintained a Boston Office while oversite for Metal Hydrides in Beverly shifted to the New York Office.

The Bombs

By the spring of 1945, the need for new projects and parts slowed down as production of the bombs became the central focus. Once the army was preparing to drop the bomb, the need to wrap up all the paperwork was underway. Between June 1945 and January 1946, final reports were requested from each vendor, and all subcontractor bills were requested, reviewed, and paid. The first book about the Manhattan Project was completed in time for distribution in early August 1945 to coincide with the dropping of the bombs. The Little Boy uranium bomb was dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, and the Fat Man plutonium bomb was dropped on Nagasaki on August 9, 1945. Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945, ending the war.

The due date for all final project reports was extended from January 1946 to March 1946. The Boston Office closed in March 1946 as the Manhattan Project work shifted to the new Atomic Energy Commission. Every office, contractor, and vendor was requested to provide lists of staff who had worked on the Manhattan Project for 6 months or more and issue an A-pin to every person on the list in recognition of their work. Stone and Webster Engineering continued working on nuclear projects across the country.

One response to “Inside the Manhattan Project: Boston as an Innovative Manhattan Project Site”

wow!! 98Poet Alix Klingenberg Interview